I loved the Berenstain Bears book series as a child. There are still stray copies in my parents’ basement, which I read to my son on our visits. I recently noticed that the series had been re-branded to one promoting Christian values (and it is so wonderful to see “God” in the title of children’s books!). A perusal of the public library yields other children’s series upholding values from various faith traditions, from Veggie Tales to DVDs of Shalom Sesame. But where are the Muslim titles?

One particularly glaring omission was during October, which has been proclaimed as “Islamic Heritage Month” in Canada. I was heartened to see a full display of titles commemorating the month at the library but then quickly shocked at the books that were selected. The books were largely written by “Orientalists” or self-confessed “Ex-Muslims.” None of those books would challenge a person to break away from their longstanding and narrow-minded beliefs on what it means to be Muslim.

Outside of “Islamic Heritage Month,” if you peruse the public library bookshelves, the selection of Muslim children’s literature remains scant. I spoke to a Toronto Public Library librarian who sits on an equity committee at her workplace who wanted to remain anonymous for this article. She explained, “It’s hard to find quality literature that is representative of diverse experiences …. The publishing industry is the first problem. Books written about diverse characters are often not written by people of color.”

Children Need to See Themselves in Books

When people of color are not given the opportunity to write our own stories, it leads to the silent erasure of our faces. My son and I were at an early years’ learning program the other day, and I watched with curiosity as my son entered the imaginative play area. He noticed some dolls of varying “races” and immediately picked the brown-skinned doll. In my day, we didn't have brown dolls, and moving beyond toys, we simply weren’t represented in the faces of our teachers, firefighters, police officers, or any of the individuals we looked up to as authority figures. This silencing continued in children’s literature. As a bookworm, the library was my haven. But I can’t recall a single time I saw a face like mine in a book I read.

This silent erasure is involved in the “identity crisis” so many Muslim youth face. I remember I used to be so ashamed that my family and I ate with our hands that I would shut the blinds at dinner time. Would it have helped to have seen brown faces in the books I read growing up? Looking back now, I’m sure my kind Greek neighbors wouldn’t have cared, but back then I was mortified at being “found out” as a brown person.

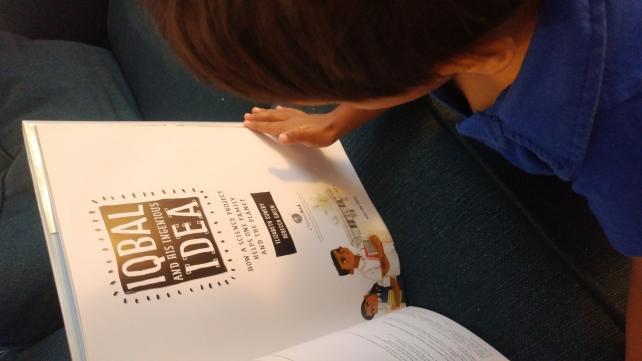

We need to increase the selection of literature offered to Muslim children and youth in our public libraries. We need more stories that celebrate what’s fun about being Muslim – Eid, family, and all that warm, gooey stuff, in addition to the great lessons and mercy and kindness in our faith. It’s easy to be deceived by a surrounding society where buying Halloween candy and sending out Valentine’s cards seem so attractive (come on, who doesn’t love lights, presents, and candy?). I recently met the author of the “Hamza” Muslim children’s series (Publisher: Deen Kids Inc.), Asna Chaudhry, at a book reading. She mentioned that she was inspired to write when she noticed that Muslim children’s literature often focused solely on teaching Islamic lessons and lacked the humor and engagement needed to attract children growing up in North America. As Dr. Sherman Jackson once stated at the Reviving the Islamic Spirit Convention, we need to create a new “Muslim cool” for our youth. And for our children, I would add we need to promote “Muslim fun.”

My sister-in-law was telling me the other day how she was trying to pump up her kids and get them excited for Eid. So she told them, “We’re going to celebrate!” Her 6-year old daughter cast a very serious glance at her mother and dryly stated, “Muslims don’t celebrate. It’s haram [forbidden].” We roared with laughter when we heard this story later around the dinner table, but it provides a truthful lens into how our children often view our faith. Beyond Eid and Ramadan, we need books that explore just the everyday experience of Muslim children and youth growing up in North America. The librarian I interviewed added, “While libraries often have some nonfiction books on holidays, it is harder to find books with protagonists with a faith identity where it’s just a regular story about life.”

Getting These Books in Libraries

Aqeela Anwar-Adhami, a university librarian in Toronto, recommends that we send in our requests to the public library with thoughtful Muslim children’s titles. Both librarians I interviewed felt that with enough requests pouring in, the public libraries will be forced to listen.

Large Muslim organizations and publishing companies can also consider putting together a Muslim children’s literature collection as a donation to the library. However, this shouldn’t be done without first having a conversation with the library. Picking a library branch situated in a neighborhood with a large Muslim demographic can help build the case.

Moreover, it’s important for library patrons to check out books that they want to keep seeing in the library; otherwise, they get taken off the library shelves.

If the lack of Muslim authors and representation at the publishing company level is the root of the problem, however, then we also need to strategically begin contacting publishing companies and demanding that greater diversity be offered. For example, Simon and Schuster recently launched an imprint, Salaam Reads (http://salaamreads.com/), which focuses solely on children’s and young adult books featuring Muslim characters. This is an incredible first step.

Advocates lament the lack of funding and recognition of the importance of arts and media for Muslim children. If we can increase the quality of Muslim children’s literature available in the library, it can help provide Muslim authors with a platform for further creative endeavors. We shouldn’t have to rely on selling Muslim literature on specialty websites or at Islamic conferences. This can become very costly for the average family. The public library is a great space to make reading accessible, and our books need to be there.

We can work together to change the landscape of what is offered in our public libraries. Books have power. The imagery in our children’s books carries more weight than we can imagine. Like my son picking the brown doll to play with, we need to provide characters in our books that resonate with our children and youth. Seeing our faces, hearing our stories – written by Muslims, for Muslims – is crucial to ensuring the healthy identity formation of our young Muslims growing up in North America.

A Step-By-Step Guide

Here are a number of ways you can increase the selection of Muslim children’s literature at your local library.

- Make a list of great Muslim children’s literature and check if your local library has them.

- Figure out how to suggest new titles at your local library (resources have been shared at the end of this article). Be prepared to provide the details of books you are recommending. This includes: title (and sub-title, if applicable), author (first and last name), publishing information (publisher, date of publication/release date), media format (book, DVD, CD, videogame, etc.), ISBN # (for books).

- For the titles that already exist at the library, check them out so they stay in circulation. (And when new titles are added, check them out as well!)

- Contact children’s publishing companies and request they feature Muslim authors.

- Contact Muslim publishing companies and organizations to see if they would like to put a collection together to donate to the library.

Farah Islam, PhD, is a mental health advocate, educator, and researcher. She explores mental health and service access in Canada's racialized and immigrant populations and orients her research and community work around breaking down the barriers of mental health stigma. She has also been a script writer for the Adam’s World video series and lives in Mississauga, Ontario with her husband and son Yusuf.

Add new comment